This week in Spain, the government submitted an ambitious plan to reach 75 per cent renewables by 2030 as part of its efforts to help the world cap average global warming at well below 2°C. Australia is being urged to do the same.

The new report released by the independent think tank ClimateWorks last weekend maps out how Australia can, and should, reach net zero emissions across its entire economy well before 2050, and as early as 2035 if capping average global warming at around 1.5°C is the goal.

Fundamental to this is the rapid transformation of the electricity grid, because a low carbon grid helps decarbonise transport and buildings, even if it means more electricity is consumed.

“Decarbonisation of electricity generation is a precondition for decarbonisation throughout other sectors,” the report says. “Electricity produced by renewable energy facilitates a shift away from fossil fuels in buildings, transport and other areas.”

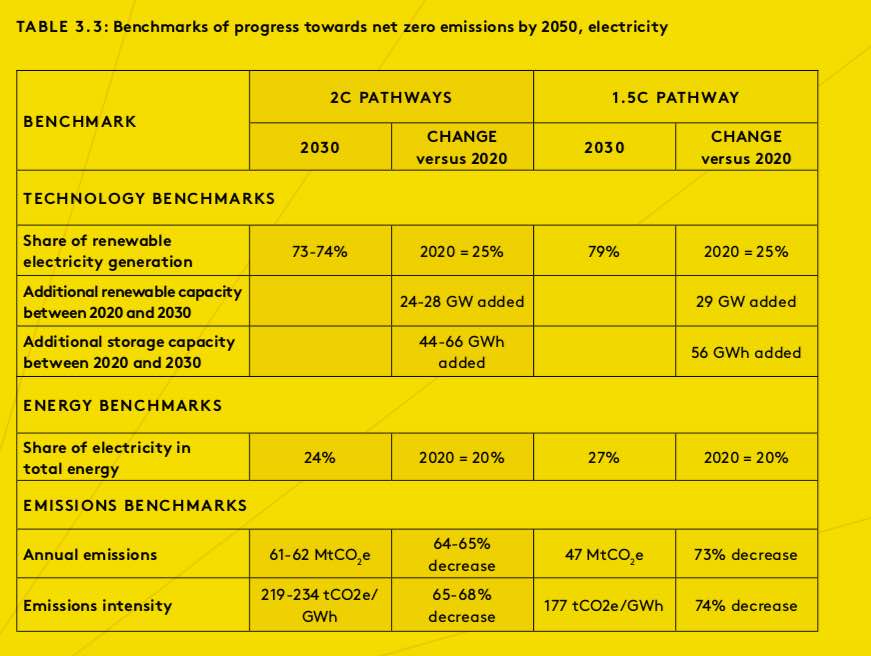

In each of the scenarios considered by ClmateWorks, Australia needs to reach around 75 per cent renewables in its electricity supply by 2030 – from 74 per cent in the 2°C scenario to 79 per cent in the 1.5°C scenario.

That’s up from 25 per cent now, and well beyond the current 50 per cent targets for 2030 by the large states such as Victoria and Queensland, even though Tasmania aims for 200 per cent by 2040, and South Australia expects to be “net” 100 per cent by 2030, and the ACT is already there.

“While the modelled benchmarks might seem ambitious, they are by no means impossible,” the report says. “The research highlights the progress being made – progress that now must be turbocharged with governments, businesses and individuals mobilising to achieve faster change than under typical market conditions.

“In short, action – the deployment of renewables,investment in research and development, the construction of transition infrastructure, the commercialisation of emerging technologies and other measures discussed in the report – cannot wait until 2030 or 2050.”

How is this to be done? According to ClimateWorks CEO Anna Skarbek, it can be done largely with existing and mature technologies – wind and solar to provide most of the “bulk generation”, and pumped hydro and battery storage to deliver much of the dispatchable energy requirements.

Is this realistic? The naysayers have always argued that wind and solar can’t power a modern economy and will be the ruin of Australia. The current Coalition government argued that Labor’s target of 50 per cent renewables would be “reckless” and economically disastrous.

But the government now assumes – in its own modest emissions targets – that the country will get 50 per cent by 2030 anyway, an indication that the 50 per cent target was not really that much of a push anyway – because the rapid uptake of distributed energy, and particularly rooftop solar, will provide a sizeable chunk of that increase.

Retiring coal generators will be replaced by the cheapest technology, which is clearly wind and solar according to the analysis by the CSIRO and the Australian Energy Market Operator, even backed up to make it “firm” and dispatchable.

AEMO, it should be noted, dials in as assumption of at least 50 per cent renewables by 2030 in the draft of its latest Integrated System Plan. In its “step change” scenario, which works out the pathway to match the aspirations of the Paris climate treaty and what scientists say we must do, i.e. get close to 1.5°C, Australia reaches 90% renewables by 2040.

Many analysts, and many big energy utilities, have pointed out that this could likely be achieved even faster, given that the AEMO and CSIRO cost assumptions are considered to be too high over what they are seeing in the market.

But Skarbek says while the market and technology costs will drive much of this adoption, it is not enough, and will require more from government and business.

“The transition will not happen in time without strong action by every level of government, businesses and individuals to support technology development, demonstration and deployment,” it says. But that does not necessarily mean subsidies, thanks to the falling cost of the key technologies.

But the major factor influencing the speed of the transition to renewable electricity is the rate at which coal generation (and then gas) exits the system.

Additional policy drivers for coal and gas closure are needed to unlock faster decarbonisation in the sector. That may be hard since the current federal government is insisting gas plays a big and expanded role as a “transition” fuel, and its insistence it is still on the lookout for “new” technologies.

The ClimateWorks scenario show that the transition to higher proportions of renewable electricity is managed via energy storage and flexible demand (such as responsive electric-vehicle charging in later years in particular).

It dials in a fair degree of solar thermal technology. Given the failure of the South Australia solar tower plan, and notwithstanding the impending pilot of Australia’s RayGen’s solar storage technology, it is likely that Australia will see more pumped hydro and batteries in the storage mix.

The study – perhaps surprisingly, despite its focus on “existing technologies” – also excludes consideration of green steel, green aluminium or green hydrogen, which would likely help reduce overall system costs by providing more renewable generation assets than needed to meet domestic demand, and providing valuable storage.

Source : RENEW ECONOMY